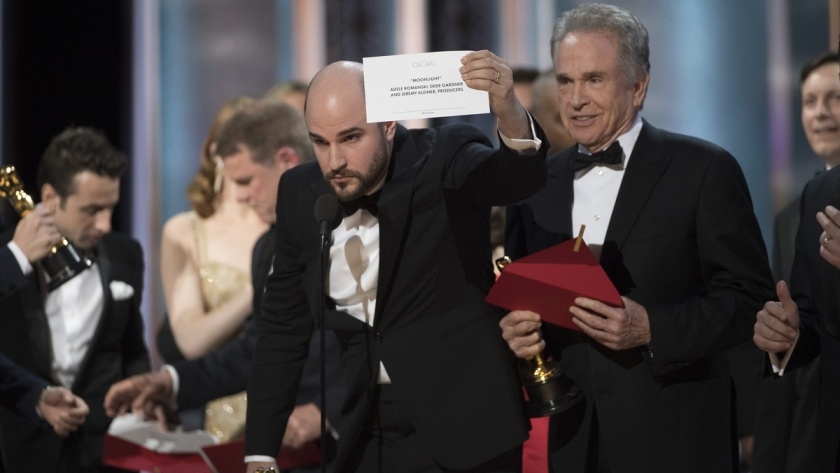

Last year, close to 33 million Americans had their TVs tuned to the Oscars and watched in shock as presenters Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty flubbed the presentation of the Oscar for Best Picture. Dunaway and Beatty, who were given the wrong envelope by the TV producers, hesitated before declaring La La Land the winner. As that movie’s producers began their acceptance speech, the Oscar show’s producers came to the stage to announce that the film Moonlight was actually the “Best Picture” of 2016. It was an odd yet compelling moment that was quite possibly the only real moment of drama in award-show history.

Although the fiasco kept people talking for days, it shouldn’t be overlooked that two more drastically different movies couldn’t be nominated for the Best Picture award. La La Land, which was actually the most-nominated film of the year’s Oscars, was a cinematically extravagant musical harking back to the Hollywood of the ’50s; while Moonlight, a socially conscious tale of race and sexuality, told the story of a young queer Black American. And although Moonlight was a noble tale, it was a small picture that lacked the pizzazz of the more exquisite La La Land. But it may not be surprising that Moonlight won the biggest award of the night, for last year was the year that many in both Hollywood and the media expressed disappointment and regret that few people of colour were being recognized in the world of film. Interestingly, Dunaway and Beatty had 50 years earlier stared in the legendary Bonnie and Clyde, a violent biopic that helped to usher in the New Hollywood era. And although it was tied for the lead of Oscar nominations for 1967, it actually lost the Best Picture award to the much different In the Heat of the Night, a Norman Jewison exploration of racial bigotry in the American South. The late ’60s were a time of racial uprising in the United States, particularly in the South, and the Oscar award show for the 1967 season aired just two days after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

I mention this allegory not to draw criticism at Hollywood’s attempt to address race in the movies but rather to note how tricky and naïve it is to attempt to define a Best Picture when politics enters the equation. Or should I say marketing, for the Academy Awards were founded in the late ’20s by the major studios as an attempt to promote their products — movies. (To this day, movies that win the big Oscar awards see an upswing at the box office after the awards show.) And politics may be a factor in this year’s Oscars ceremony, given the #MeToo movement.

The history of the Oscars have left many people scratching their heads. How did Citizen Kane, long heralded by many as the best movie to ever come out of Hollywood, lose the Best Picture Oscar to How Green Was My Valley, a lesser-quality John Ford picture? (The answer lies possibly in the meddling of a disgruntled newspaper mogul.) How is it that the Master of Suspense, Alfred Hitchcock, never won a competitive Oscar? And somebody explain to me how the mechanical Crash earned the Best Picture over the more artful Brokeback Mountain and suspenseful Munich. And then there’s the year 1977, in which Annie Hall, a masterful comedy and possibly Woody Allen’s best cinematic effort, won the Best Picture Oscar over Star Wars, George Lucas’s sci fi opus that sourced ancient myths and epics to reimagine the ’40s and ’50s low-budget shorts that Lucas idolized as a kid. Both movies are spectacular, yet forcing them to compete within the same set of artistic aesthetics is absurd.

But that’s not to say that the Oscars always get things wrong. Take the case of Francis Ford Coppola, who directed, produced, and wrote The Godfather, Part II while editing The Conversation at night. Both movies were nominated for multiple Oscars for the 1974 Oscar season — one of them winning Best Picture — and both have since been hailed as well-received masterpieces.

I’m thoroughly amazed how seriously people take the Oscars, for I’m confused as to why people watch it. Do people watch the show to see who wins the awards, or do they watch to see what the female actors (why do people still say “actress”?) are wearing? Do they watch to hear the jokes the host will say at the beginning? Or do they watch because they want to see celebrities act as themselves? Or perhaps they want to see moments as real as the Dunaway and Beatty Oscar flub. I’m not sure. I’ve sat through Oscar shows, and they’re three- to four-hour bore feasts: awards are given periodically, while in between, songs are sung and other unrelated topics explored. It’s not something I enjoy, and it’s an approach that has been expanded to other award shows. I have never seen the Grammys, I would be shocked if anybody watches the Canadian Screen Awards, and the Golden Globes are dull. I now see award shows like the Oscars as the original reality TV shows: People enjoy watching them in the hopes of seeing the kind of unscripted drama that happened during last year’s Oscars. Oscar spectators, in a sense, aren’t all that different than people who watch sports on TV. It’s just the venue that’s different.

As I finish writing this article, the Oscars have probably finished, and I have no idea who won what. Nor do I care. Instead of watching the Oscars, I streamed a horrible movie and listened to a podcast. But I think I share my lack of Oscar enthusiasm with George C Scott, who died in 1999. A respected and intense thespian of both the stage and screen, Scott may be best remembered for his roles in Dr. Strangelove and Patton. And when he was nominated for his performance of the titular character in the latter movie in 1971, he warned the Oscar committee that were he to win, he would reject his award on philosophical grounds. “The whole thing is a goddamn meat parade,” Scott was reported to have said. “I don’t want to be a part of it.” Surprisingly, given his lacklustre attitude, Scott won the award anyway. (His performance was good. He put a tremendous amount of effort and research to create an effective portrayal.)

At the time his win was announced, Scott was asleep at home. I admire Scott for his attitude. He made Oscar ennui cool. You have my back, George.