About three years ago, I began using Goodreads to track my reading habits. Goodreads, which allows you to search for books to read, rate books you’ve read, and set a yearly goal of the number of books you want to read, is the Facebook solution for people who at times prefer the company of a good book. In fact, when you open a Goodreads account, it will automatically import any of your Facebook friends who are also on Goodreads.

I’ve been going over my Goodreads account to review my reading habits over the past three years. I’m surprised, first of all, at how much my reading level has dropped off since my 20s, when I was reading perhaps 25 or more books per year. And interestingly, I am reading mostly fiction, with on average one or two non-fiction books thrown in.

My non-fiction reading falls into two broad categories. I’m apparently attracted either to biographies of performers — including writers (I read a decent bio of J.D. Salinger that suffered from its subject’s alusiveness), musicians (I was disappointed to hear that drummer Keith Moon wasn’t all that likable), and athletes (I loved Norman Mailer’s take on Muhammad Ali) — or to non fiction that has a sociological or anthropological outlook to human sexuality and intimacy. (Did I really follow up a book about polyamory with a book about living solo? Aren’t they polar opposites, and what does it say about me?)

But I’m devouring mostly novels; most notably, I’m latching onto certain authors, reading a multiplicity of their works. This isn’t new to me: in my 20s, I read a plethora of Canadian authors, coming to admire the works of Margaret Atwood, Margaret Laurence, Mordecai Richler, David Adams Richards, and Jack Hodgins. Or there was my fascination with Kurt Vonnegut and George Orwell.

But my reading preferences are evolving. I’m currently drawn to authors who either have a very distinct writing styles (Cormac McCarthy, Jose Saramago) or write within a distinct genre (Salman Rushdie and Gabriel Garcia Marquez and magical realism). And yet again, I’m drawn to authors who write brutally violent stories (McCarthy and his bloody Westerns, John Ajvide Lindqvist and his shocking horror tales). And then again I’m attracted to authors who write about mistaken or hidden identities and twist endings (Ann-Marie MacDonald and Ian McEwan).

My mother, who follows me on Goodreads, refuses to read many of the novels I read, stating that they are violent, dark, and sick. I beg to differ. I think that what I read, despite their occasional dips into the macabre, are thoughtful didactic pieces of art. So I’d like to take the time go into detail about three authors with whom I’m currently obsessed — McCarthy, Rushdie, Lindqvist — to see if I can defend my current aesthetic tastes.

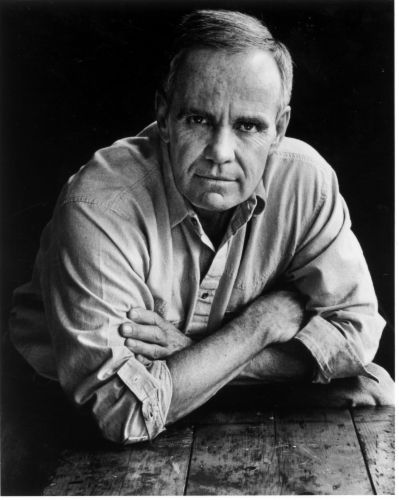

Cormac McCarthy

I first read McCarthy about four years ago, when I stumbled on his post-apocalyptic novel, The Road, set in a near future when an unnamed catastrophe kills almost all plant and animal life. The two unnamed protagonists, a father and his young son, walk along a road, the ground grey and void of any scenery; the only precipitation is a grey, snow-like ash. The father, hoping to make it south to presumably warmer grounds and water, carries their meager belongings in a shopping cart. The father, telling his son that they are “good guys,” warns his son to beware of dangerous people who may be shadowing them. The dangerous people, it turns out, are other survivors who have turned to cannibalism as a food source. The father carries a revolver with only a few bullets to protect themselves. When the father dies, the boy must fend for himself.

And this was my introduction to McCarthy, a spooky, depressing tale that earned him the 2007 Pulitzer Prize. I was hypnotized by McCarthy’s writing style, which I would later learn isn’t unique to this novel. But this style — including the omission of almost all punctuation typical to the English language; short simple, albeit beautifully composed sentences; and quick, rhythmically jabbed dialogue that in combination make it difficult to identify the speaker — added to the claustrophobic terror of The Road. When I was reading The Road, I noted that the omission of quotation marks to offset the accented, prompt dialogue between the father and son –remember that we never learn their names — made me feel that I was reading a story that succeeded to do in book form what Night of the Living Dead had succeeded in doing in cinematographic form some four decades previous: create a scary, bone-chilling small space in which the characters must struggle to fight from being eaten.

But McCarthy’s writing style is universally consistent among all of his novels, including his critically acclaimed historical Western, Blood Meridian, which follows a teenaged Tennessee boy known only as The Kid, who joins a vigilante gang of guns-for-hire called the Glanton Gang, an actual historical gang that travelled along the U.S.-Mexico border to kill and scalp Native North Americans. The Kid, who early on in the novel had proven himself a formidable bar fighter, joins the gang after spending time in a Mexican jail with his older, earless friend, Toadvine (they had participated in a slaughter of Native Mexicans together). When they join the gang, The Kid is reintroduced to Judge Holden, whom The Kid once saw encourage a church congregation to kill the preacher after Holden accuses the preacher of raping both a girl and a goat. Naturally, Holden, a seven-foot giant, proves himself the most violent member of the gang. As the gang expands their exploits beyond scalping to outright robbery and murder of anybody they encounter, they are eventually caught; most of the gang is slaughtered. Both Holden and The Kid escape and during a chance meeting years later in front of a brothel, and a naked Holden, quite possibly a pedophile, attacks The Kid in an outhouse.

McCarthy again uses his sparse, beautiful writing, almost zero punctuation, and crisp, confusing dialogue, to alienate the reader in an almost Brechtian technique, making the reader think and ponder about about the violence of American history. Yet McCarthy, even with all his violence, shows beauty in his writing. Just picture the last scene in The Crossing, a novel featuring a teenage boy who rescues a pregnant wolf from a trap and takes it to Mexico, where it came from. After a months-long ordeal, during which the kid has to kill the wolf after it’s been forced into dog fighting by bandits and learns of the murder of his parents by robbers, the kid is approached by a starving dog looking for help. The kid quickly regrets kicking the dog:

“He walked out. A cold wind was coming off the mountains. It was shearing off the western slopes of the continent where the summer snow lay above the timberline and it was crossing through the high fir forests and among the poles of the aspens and it was sweeping over the desert plain below. It had ceased raining in the night and he walked out on the road and called for the dog. He called and called. Standing in that inexplicable darkness. Where there was no sound anywhere save only the wind. After a while he sat in the road. He took off his hat and placed it on the tarmac before him and he bowed his head and held his face in his hands and wept. He sat there for a long time and after a while the east did gray and after a while the right and godmade sun did rise, once again, for all and without distinction.”

And the books ends just like that. For McCarthy, despite his themes of graphic violence, has a touch of sentimentality to his writing. Is that what I’m attracted to? Or is it his aloof, alienating writing style? Or maybe both?

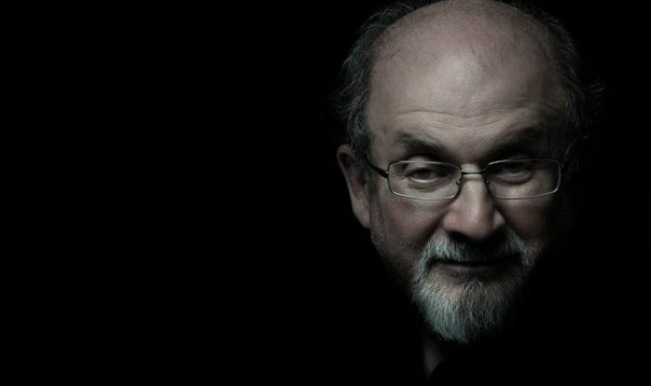

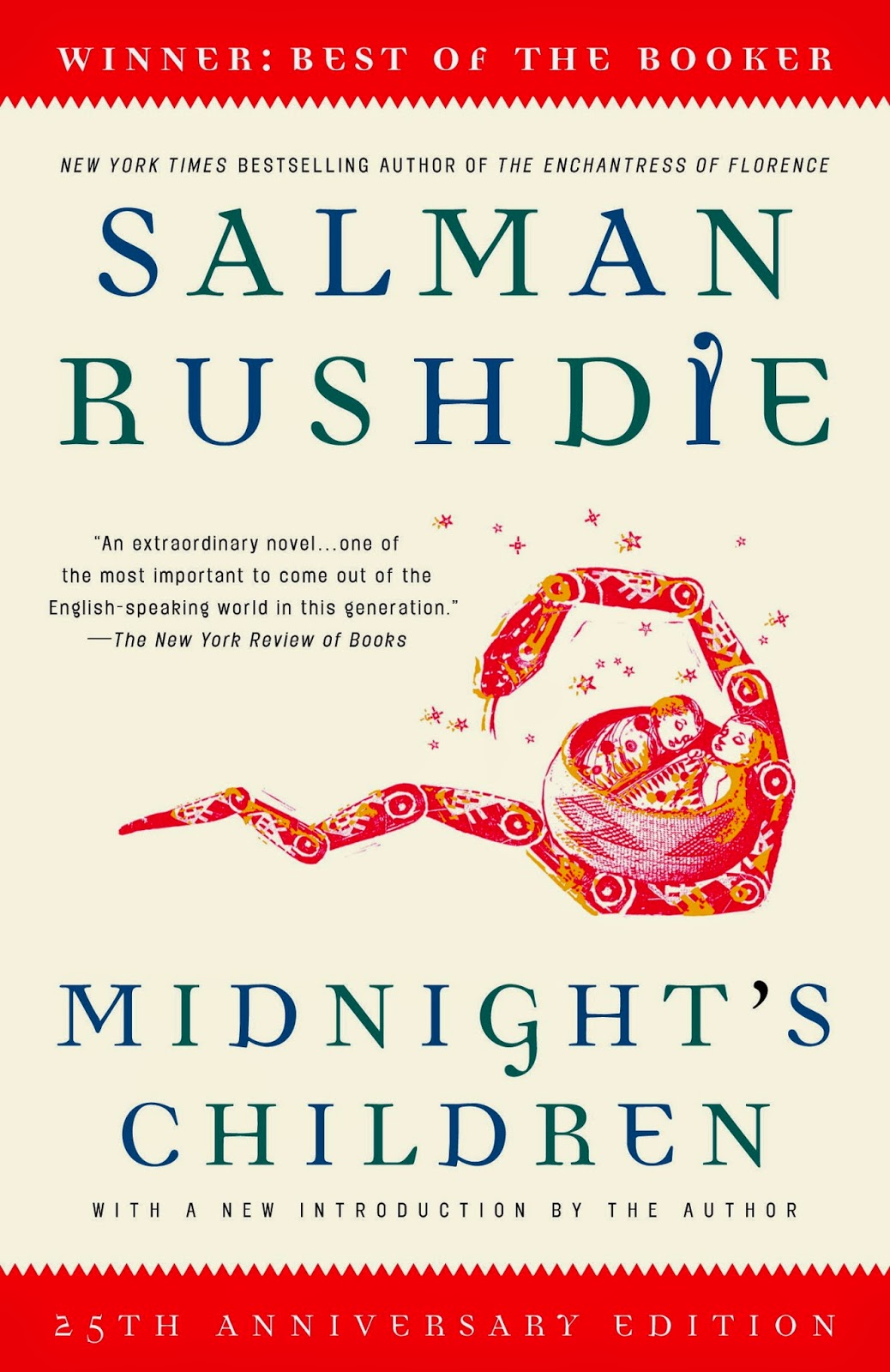

Salman Rushdie

I have to admit that I avoided Rushdie for years, for I was a 13-year-old kid when Rushdie’s life was threatened by the Ayatollah Khomeini, who issued a fatwa (death threat) after the publication of Rushdie’s 1988 novel, The Satanic Verses, a book that I’m planning on reading later this year. The stir that it caused, along with Rushdie’s subsequent years-long hiding, jarred me for a long time because I thought I would have no entrance to the author’s writing. I have little understanding of the Islam religion, nor am I knowledgeable about India, the setting of many of Rushdie’s novels. However, after hearing Rushdie praised as an intellect and excellent writer, I decided to give him a chance and chose to read Midnight’s Children, Rushdie’s 1981 Booker Prize–winning novel about Indian children born on the very day of India’s independence from the UK.

Midnight’s Children is an epic tale of Saleem Sinai, who was born at the stroke of midnight on August 15, 1947, the exact moment in time when the British partitioned the Indian subcontinent into the independent states of India and Pakistan. As Saleem grows up, he discovers that he has telepathic abilities, a skill that throughout most of his childhood he struggles to keep secret. Additionally, he has an enormous nose that gives him an excellent sense of smell. Saleem was placed into the wrong family by his nurse; instead, he is placed with the family of his arch nemesis Shiva, who is placed with Saleem’s family. Shiva, who has equally strong magical powers –every child born in India that day has magical powers — becomes bitter when he realizes that he was placed into a poor family instead of the middle-class family that was rightfully his.

As Saleem learns to control his powers, he telepathically communicates with every other magically gifted Indian child born that day in order to bond over their shared powers; he bonds most closely with Parvati-the-witch, who has the ability to make herself disappear. The story follows Saleem as he experiences India’s turmoil through its first three decades of independence. Saleem’s family becomes part of the Muslim exodus to Pakistan and as a young man is forced to fight on behalf of the independence forces of what would eventually become Bangladesh. He develops temporary amnesia until he returns to India, where he and the other magically gifted kids become victims of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency and her son Sanjay’s Cleansing, which, according to Rushdie, was conceived to sterilize the magically gifted kids (now adults) and rob them of their powers.

Midnight’s Children is clearly set in the genre of magical realism, in which supernatural, over-the-top events are downplayed and ordinary events — in this case India’s turbulent first three decades of independence — are exaggerated. It’s a technique that Rushdie uses to great effect to make political and social commentary about the limitations of Indian democracy and its caste system. But who can deny the beauty of Rushdie’s prose as Saleem describes the abuse of power of Shiva, who at this point had become a major in the Indian army. Shiva becomes a womanizer, and Saleem recounts,

“And certainly there were children. The spawn of illicit midnights. Beautiful bouncing infants secure in the cradles of the rich. Strewing bastards across the map of India, the war hero went his way; but (and this, too, is what he told Parvati) he suffered from the curious fault of losing interest in anyone who became pregnant; no matter how beautiful sensuous loving they were, he deserted the bedrooms of all who bore his children; and lovely ladies with red-rimmed eyes were obliged to persuade their cuckolded husbands that yes, of course, it’s your baby, darling, life-of-mine, doesn’t it look just like you, and of course I’m not sad, why should I be, these are tears of joy.”

So why am I a fan of Rushdie, despite his description of violence and human rights violations? Perhaps it’s because Rushdie, like McCarthy, uses literary techniques to purposely describe the violence of the world while wrapping it up in exquisitely beautiful prose, to make the reader reflect. And later on I read Rushdie’s Grimus, another fantastical tale about a Flapping Eagle, who gains the power of flight and immortality. When he travels to Calf Island to regain his mortality and reunite with his sister, he becomes engaged in perilous quests that make him question his humanity. It was a tale I was less fond of, but it’s Rushdie’s first novel and a hint of the masterful skills that he would later develop.

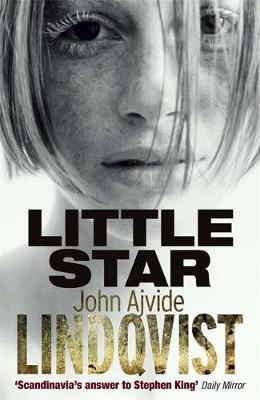

John Ajvide Lindqvist

I was first introduced to Lindqvist when I saw the Swedish vampire horror movie Let the Right One In, the movie adaptation of Linqvist’s book of the same name. It’s a beautifully shot, haunting horror that features the Scandinavian snow as its principle star. (The movie was faithfully rebooted in Hollywood two years later with the title Let Me In. Both movies are well worth seeing.) I was so captivated by the story of a bullied 12-year-old boy and a centuries-old vampire trapped in the body of a pre-adolescent girl that I immediately discovered that the movie was based on a novel by Lindqvist and got busy reading.

Let Me In opens with Oskar, a small weak socially awkward preteen who lives with his single mother in a small town in Sweden. It doesn’t help that Oskar has a morbid fascination with death and violence: in the opening scene, he quizzes a police officer visiting Oksar’s class about recent murders. Oskar’s seemingly clueless about how he’s perceived by others, and it’s this innocence that earns him the attention of the school bullies, who relentlessly torment Oskar both physically and emotionally. Because Oskar is so socially isolated, he spends his free time alone on the playground in front of his apartment building. One day he is befriended there by his new neighbour, Eli, who is seemingly a 12-year-old girl living with her father. Eli only comes out at night, never wears a winter jacket or boots (despite the Swedish winter) and keeps to herself. Oskar and Eli are attracted to each other and to their seemingly similar isolation and quickly start up a conversation. Eli is quick to encourage Oskar to use violence to fight back against his tormentors. Oskar does, including setting their desks on fire, encouraging only more bullying.

But Eli’s casual offering of violence as a solution comes with a dark secret, for she is actually a centuries-old vampire who relies on human blood to live. And the man she lives with isn’t her father but rather a pedophile who kills people for their blood in hopes of receiving sexual favours from Eli. When he is caught by the police and kills himself rather than give up Eli’s secret, Eli must fend for herself. She attempts to get the blood from a local woman, who survives the attack and sets herself on fire by looking at the sun rather than turn into a vampire. And when Oskar’s tormentors attempt one final attack — drowning Oskar in the public pool — Eli kills the kids, their heads and limbs sinking in the pool. The novel ends with Eli and Oskar running away together.

And that was my introduction to Lindqvist, who used a vampire story to explore diverse themes such as bullying, pedophilia, single parents, murder, and violence. Yet it’s not his most violent story. There is also Little Star, which follows Theres, who as a young girl, was found abandoned in the woods by a musician. He takes her home and locks her in his basement, where he and his wife raise her in isolation. Theres, either because of her isolation or because of mental illness — she never does learn to speak in full sentences — kills her adoptive parents by smashing their heads in with a hammer and drill. When their adult son, Jerry, comes over for a visit, he discovers the mess:

“Theres was kneeling in the blood next to what remained of Laila’s head, which was slightly more than in the case of Lennart. In her hand she held the drill; the battery was so run down that the bit was hardly rotating at all. With the last scrap of power left in the machine she was busy boring her way in behind Laila’s ear. A little pearl earring in Laila’s earlobe vibrated as the drill laboriously worked its way through the bone. Theres struggled and tugged, changed the direction of the drill and managed to pull it out, wiped the blood from her eyes and reached for the saw … ‘Theres,’ (Jerry) said, his voice almost steady. ‘Sis. What the fuck have you done? Why have you done this?’ Theres lowered the saw and her eyes slid from Laila to Lennart, over the bits of their heads strewn all around her. ‘Love,’ she said, ‘not there'”

There is little doubt that this is perhaps the most violent story I have ever read. Yet the above passage isn’t the most violent in the book, for as Therse progresses throughout her teens, Jerry places Theres into a televised singing contest (think American Idol), where Theres develops a cult following among teen girls who are attracted to Theres’s zombie-like demeanour. Eventually, Theres and her followers meet; and Theres, mad because of the sexual advances of a record producer who had attempted to rape her (Theres eventually killed him), takes her followers to a rock concert, where they murder hundreds of people with hammers and drills.

The novel is extremely violent and Linqvist’s themes — murder, pedophilia, isolation, despair — almost universally span his novels. And although Linqvist lacks the power of prose that both McCarthy and Rushdie have in spades, Linqvist is able to make thoughtful connections between isolation, ennui, and violent behaviour. For recent acts that have made the news — including school shootings and incels — seem to reflect the motifs that Linqvist explores in his novels. I may be attracted to Linqvist because I recognize that the horror genre explores the hidden truth that is far too scary for many people to talk about openly.

I Think I Understand Now

I’m not a violent person, nor do I advocate violence. I do, however, appreciate well-crafted, meaningful tales that can perhaps teach me something. And that is the love I have for these writers. And if an author can leave me in better shape than before I started to read him or her, I’m happy. That’s all I ask for. And to my mother, who says I read dark, scary novels: I am learning something. I’m learning to recognize the animal violence in people.

You must be logged in to post a comment.